Making Hay Monday – May 8th 2023

Making Hay Monday – May 8th 2023

High-level macro-market insights, actionable economic forecasts, and plenty of friendly candor to give you a fighting chance in the day’s financial fray.

“This part of the [banking] crisis is over.” -Jamie Dimon

“We are kidding ourselves if we think there are only four problem banks in the country.” -Bill Isaac, former head of the FDIC

Doubled-Troubled Asset Relief Program?

Let me state right up front that I am a fan of Jamie Dimon. He and I worked together in the 1990s during my days at Smith Barney, though, in fairness, it was more like I worked for him. However, I was representing our advisor force in those days and I always found him to be a great listener, especially on ideas that made sense for the key constituents: clients, financial advisors, and the firm.

When he was unceremoniously and, I believe, unfairly fired by Citigroup in 1998, it was a wake-up call for me. At that time, I had nearly all of my financial net worth in a stock plan made up entirely of Citi stock. Jamie’s dismissal alarmed me so much that I began a multi-year exit from that plan, disposing of nearly all of my holdings. Once the financial crisis of 2008 hit, those shares would vaporize from the 50s all the way down to $1 per share. In fact, they likely would have gone to zero without the government’s Troubled Asset Relief Program or TARP. Even today, Citigroup stock is less than 10% of what it was trading for in early 2007. (As you will soon read, it’s possible that the TARP is about to make a repeat performance.)

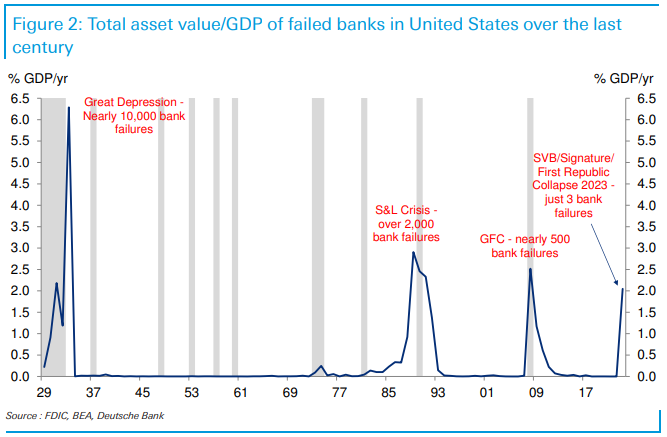

The reason I made that brief trip down my personal memory lane is because of the parallels with today. Unless you’ve been hiking in Kathmandu for the last two months, with no cell coverage (do they have cell service in the Himalayas?), you’re aware that when it comes to the banking industry, it’s déjà vu early 2008 all over again. Three of the largest bank failures in U.S. history have already occurred. Based on the stock price action of several other leading regional banks, there may be more on the way.

Pac West

Huntington

Western Alliance

US Bank

One that may be the most concerning is super-regional U.S. Bank. Its stock chart indicates it is dangerously close to breaking the critical three-support level often discussed in these pages. (For newer readers, this is my theory, also shared by superstar investor Paul Tudor Jones, that when a long-existing trading range is broken, either up or down, the stock in question will continue in that direction, often significantly.)

To learn more about Evergreen Gavekal, where the Haymaker himself serves as Co-CIO, click below.

In looking at several of the charts above, you’ll notice in the case of Pac West Bank considerable pain could have been avoided by exiting when it broke below three-year support at around 15. This was also the Covid low and any stock taking that out should be looked at askance right now. Interestingly, with the three big collapses mentioned above — specifically, Silicon Valley Bank, Signature Bank and First Republic, the violation of critical support levels also provided timely “get-out” signals. (It’s fair to note someone tracking these would have needed to move very quickly, especially with the first two.)

The good news is that for the regional bank stock index/ETF, support has not been broken — yet. The additional positive is that Friday brought a ferocious rally in this badly mauled sub-sector, with that ETF (KRE) up 6.3%. The not so hot news is that it is now well below where it traded at a number of years ago… as in 17!

Encouragingly, Jamie Dimon weighed in early last week that, in his view, the worst of the banking crisis has passed, per the above quote. When I was interviewed (or “Linterviewed”) by David Lin on Wednesday, he asked me if I agreed with Jamie on that score. Based on what you read at this article’s opening, it wasn’t easy for me to disagree… not to mention that he’s America’s smartest and richest banker. In fact, he’s such a tour de force at his bank that I think you could almost replace the “JP” and rename it “Jamie Morgan”.

However, maybe he’s right and Thursday was the bottom. Color me skeptical and contributing to my view was a podcast I listened to last week between Erik Townsend and Chris Whalen. Frankly, I was only vaguely familiar with Chris a few months ago. Yet, I was aware he was one of the few banking experts who was warning early on that higher interest rates were a grave threat to many banks. In reality, most pundits felt rising yields was a positive for this sector because it gave lenders the chance to earn much higher rates on their assets, like government bonds, while keeping their borrowing (deposit) rates at miserly levels.

When Erik asked if the crisis is over, Chris was blunt and adamant it is not. His exact quote was “there is a significant crisis risk”. To avoid the banks taking “terrible hits” on their portfolio, threatening their solvency due the highly leveraged nature of the banking system, they need a radical rescue program. He believes the Fed will need to not only lend against the banks’ enormous government bond holdings at face value, as it is now doing, it also needs to provide bargain financing, like 2%, which it is not. Thus, if they can borrow from the government at, say, 2% and lend out at 6% to 7%, they can get healthy again over time. “Time” is one of his key points: it’s going to take a lot of that — and the just-mentioned positive spread — to reliquify the banking system. (In a CNBC interview last week, Chris opined that “all banks are suspect at this point”. He further stated that more of them will fail and that their funding costs are likely to double this quarter as they frantically raise rates to hold onto deposits.)

As far as economic impacts, he is convinced this escalating crisis will be a major drag. As most readers know, this is a view I share, particularly due to the nasty combination of a collapsing money supply and plunging money velocity. (Also, like me he’s extremely worried about commercial real estate (CRE); 70% of loans to CRE are held by small- and mid-sized banks.)

Chris didn’t specifically mention the velocity aspect, but he is certain that the stress most banks are under right now will hurt lending. In my mind, that’s the flip side of the velocity coin. In short, deposits either flee because of solvency fears or to earn higher yields in government securities; as a result banks have much less capital to lend; small businesses, the heartbeat of the economy, lose access to financing; as a consequence, defaults rise, further intensifying the banking stress; this causes banks to become even more cautious; and the doom-loop continues.

The net effect is that money velocity — i.e., it’s turnover rate — does a faceplant. As a refresher, total economic activity, or nominal GDP, is a function of money supply times velocity. With both now in downtrends, that is a serious threat to the economy. It remains my view that there is precious little focus on this mega-challenge. One of the few who is pounding the table on it is the venerable Lacy Hunt, that rare combination of an economist and a wildly successful bond manager at Hoisington, the firm he co-founded.

Chris’s way-below-market financing plan for the banks could certainly work, but there is one big problem with that in my mind. The Fed is already paying around five percent on the four trillion on deposit with it from banks and money funds. That’s about a $200 billion hit to the Treasury and, of course, taxpayers. If the Fed now needs to lend a few trillion to banks at 2% while paying 5%, it will serve to weaken the Federal governments already abysmal financial condition.

A better option may be to restart the old TARP mechanism mentioned at the outset of this note. While it was highly controversial, even detested, it worked wonderfully and produced a $30 billion dollar windfall for taxpayers (including interest earned and capital gains). When it was first announced, I was in my usual lonely position of supporting it and saying it would be a money maker with the much more important benefit of preventing a financial Armageddon.

That view attracted considerable derision, a reaction with which I am very accustomed. The reason it was so lucrative was because the Feds also took warrants on the shares in the participating financial institutions it was lending to (which was about 80% of them, including almost all of the biggest banks.) Thanks to the fact solvency fears had totally nuked their stock prices, the government was getting warrants (like call options) at fantastically undervalued levels. Once TARP kicked in, along with a relaxation of accounting rules on mark-to-market losses, the financial stocks exploded higher, creating almost instantaneous profits for the Treasury. Back then, it was also borrowing at close to zero, so the high interest rate it earned on the loans was another source of lush income for the government.

Regardless of the actual bail-out structure, like Chris, I do think something dramatic will need to be put in place. The short sellers are attacking any bank that looks vulnerable, and that’s a long list. As he noted, when deposit flight forces them to sell their holding at a loss, they are effectively being decapitalized. All of these negative forces tend to feed on themselves until truly extreme support measures are employed. Naturally, the Fed is the only entity with the firepower to effectuate a rescue on this scale.

One of the saddest and most puzzling aspects of this crisis is how cheap it was, prior to the Fed’s tightening campaign, for banks to hedge against much higher rates. In 2019, it was possible to buy a three-year interest rate cap at 3% on $100 million for a mere $98,000. Now, that cost is $3½ million. A rational observer would think any entity with the kind of existential risks to a much higher cost of money would be all over that type of coverage. But, then again, Powell & Co. was telling the world back in 2021 that it was “not even thinking about thinking about raising rates”, giving the impression that essentially free money would continue indefinitely. It was a terrible call, right up there with Mr. Powell’s repeated assurances that year about inflation being transitory.

If there is a rescue plan in the works, that would clearly be very bullish for many bombed-out financial stocks. The tricky part is how bad it needs to get to cause the Fed and the Treasury to take their triage efforts to the next level. At this point, I don’t think the pain is intense enough yet. But a few more major failures and the time will be at hand for another government hand-out. Hopefully, it will get paid to do so as it did — cleverly and most unusually — back in 2009.

Champions

Mike O’Rourke, the author of one of my daily reads, has wryly observed the market’s “Magnificent Seven”, comprised of AAPL, MSFT, AMZN, GOOG, TSLA, NVDA, and META, has produced 110% of the S&P 500’s return so far this year. In other words, collectively, the other 493 stocks are in the red. That’s another indicator of the U.S. equity market’s ominously narrow leadership that is one of my current pet peeves.

Fortunately, for broad-minded investors — perhaps, make that abroad-minded investors — there are far better opportunities overseas. On that score, you may have noticed Warren Buffett traveled to Japan last month. Knowing the Oracle’s fondness for staying close to home given his nonagenarian status, that speaks volumes on its own. Adding to that, he ventured those many thousands of miles away from Omaha while disclosing an increase in Berkshire Hathaway’s holdings in the Land of the Setting Yen. Actually, the weak yen may be a catalyzing factor in his stepped up ownership of Japanese companies. This is because it makes it even cheaper to buy them in U.S. dollars, and a weak currency makes Japan’s exporters that much more competitive. Further, I’d venture that it has much to do with how inexpensively that market trades versus American shares. (By the way, he’s also stated that these large and highly diversified Japanese companies have similarities to his beloved Berkshire.)

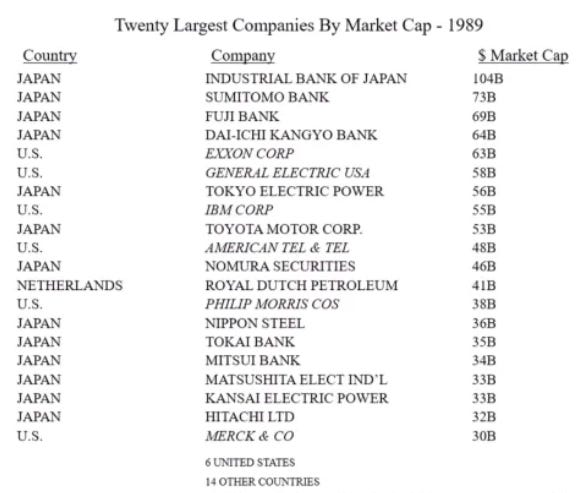

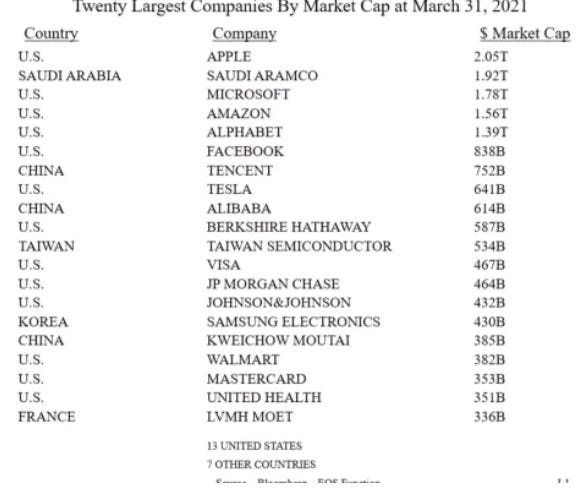

For bulls on Japan, including the Haymaker, it’s certainly fair to concede stocks over there have been alluringly cheap for a many years. This is in contrast to the late 1980s when Japanese stocks were engulfed in a bubble that made the U.S. tech mania 10 years later look like a subdued bull market. Mr. Buffett actually showed the below table of the top 20 most highly valued companies in 1989 at his 2021 shareholders gala, often referred to as the Woodstock of Capitalism. (Fortunately, no attendees have ever been reported to have overdosed on Cherry Coke or See’s Candy.) As you can see, 34 years ago, the Top-20 list was heavily dominated by Japanese stocks. Come 2021, nary a one was domiciled in Japan.

Illustrating how hazardous to one’s wealth it is to ignore bubbles — especially, of the monster kind — the Nikkei today remains below the peak of almost 40,000 it hit in early 1990. In other words, even after 33 years, it still hasn’t made a new all-time high. However, back in the fall of 2020, it did decisively break out of the trading band that had been in place since 1993. In other words, it achieved a range expansion out of a 27-year base. As I’ve often conveyed in these pages, the longer the trading range, the more impressive the breakout. Since then, it’s risen another 23%. That’s certainly respectable, especially if you add in dividends, but it’s not spectacular. Accordingly, valuations remain extremely compelling. This is particularly the case with one of my favorite fundamental metrics: the price-to-sales ratio. It’s not uncommon to find blue-chip Japanese companies trading at 40% to 60% of sales per share. Overall, the Nikkei now trades at 1.25 times sales versus the S&P’s average ratio of 2.3 times.

A few weeks back I wrote that I would try to publish a list of global stocks recently making new three-year highs. It’s been a project because there is no program we’ve found yet that automates this process (maybe we’ll be able to harness AI on this someday). Additionally, I feel it’s necessary to screen out those companies that are in long-term uptrends, leaving their stocks looking quite extended. Hopefully, we can run this soon, perhaps even next week. Please realize that it won’t be a recommended list, just a collection of names on which you may want to do further research.

The reason I bring this up is that doing this study created two surprises:

- 1. The first was how many stocks are making fairly new three-year highs in what has been a fairly nasty global bear market, notwithstanding the relief rally that began last fall.

- 2. The other was how many Japanese stocks made the cut.

In my experience, one of the best ways to make money with equities is to buy undervalued issues that have broken their down- or sideways-trends (which is usually how they got cheap in the first place) and are now showing upside momentum. Three-year breakouts are the best way I’ve found to isolate those, though, for sure not the only one.

Once again, the longer the trading range, the more significant the breakout. Great examples of this are what happened to both the S&P overall, and Microsoft, particularly, in 2013. The latter was a wonderfully lucrative instance of a value stock (it was trading for about 10 times earnings back then) becoming a growth stock. In MSFT’s case, it has been a multi-year return to its former glory, though it’s valuation remains far more reasonable than in early 2000 when it exceeded a 70 P/E.

If you think Mr. Buffett and I are onto something, there are some ETFs that allow you to easily participate. One of the leading iterations also had its big breakout in late 2020. However, since then, it has pretty much gone sideways, lagging the Nikkei itself. You can either view that as a positive (very cheap) or a negative (poor relative strength).

The other option would be to check out our breakout list. We’ll give you an assist by indicating which are Japanese. We’ll also include P/Es for each name on there. Befitting my innate contrarian nature, I have an affinity for those with modest multiples. By the way, that is the case with the Japanese conglomerates which Berkshire is accumulating.

In addition to the fact that Japan has largely been a value-trap for years, if not decades, its companies have often earned deficient returns on shareholder capital. Most management teams have also been highly resistant to improving corporate governance practices. Additionally, for better or worse, mostly the latter when money was virtually free, Japanese companies have eschewed repurchasing their own shares. This is in vivid contrast to the U.S., where buybacks have been not only used, but often over-used. In recent years, however, there are signs these drags are lessening, but things in Japan move at the speed of the glaciers on Mount Fuji.

Despite those considerations, my advice is to go East, young investor! As in, way, way East. In my mind, the odds of the Japanese stock market greatly outperforming the U.S. market over the balance of the decade are very high. The fact that so few American investors have exposure to it only reinforces my confidence — and I think it should yours, as well. In other words, “Calling All Contrarians!”

Champions List

For capital appreciation:

Japanese stock market

Telecommunications equipment stocks

Select financial stocks

U.S. Large Cap Value

U.S. GARP (Growth At A Reasonable Price) stocks

Oil and gas producer equities (both domestic and international)

U.S. Oil Field Services companies

Japanese stock market

S. Korean stock market

Physical Uranium

Swiss francs

Copper-producing stocks

For income:

Certain fixed-to-floating rate preferred stocks

Select LNG shipping companies

Emerging Market debt closed-end funds

Mortgage REITs

ETFs of government guaranteed mortgage-backed securities (alternative approach)

Top-tier midstream companies (energy infrastructure such as pipelines)

BB-rated energy producer bonds due in five to ten years

Select energy mineral rights trusts

BB-rated intermediate term bonds from companies on positive credit watch

Contenders

The swan-dive by the U.S. dollar (USD) last fall has reduced the appeal of many overseas currencies, in my view. That’s true even of the Swiss franc which has a long list of inherent strengths. Long-term, I believe it will appreciate versus the greenback. For now, though, it’s vulnerable to a pull-back, in my opinion. For those who want to retain a hedge against the USD’s structural debasement, sitting tight makes sense.

Swiss francs

Singaporean stock market

Short-intermediate Treasuries (i.e., three-to-five year maturities)

Gold & gold mining stocks

Intermediate Treasury bonds

European banks

Small cap value

Mid cap value

Select large gap growth stocks

Utility stocks

Down for the Count

Lately, it’s been another triumph of hope over experience for some of the more infamous famous meme stocks. Accordingly, I’d revisit those either to be taking profits or instituting downside hedges (such as puts). This group can be very tricky to outright short, including outrageously high borrowing costs. Regardless, at least two of them look to have tremendous downside, particularly should we be entering another risk-off phase, as I believe likely.

Meme stocks (especially those that have soared lately on debatably bullish news)

Financial companies that have escalating bank run risks

Electric Vehicle (EV) stocks

The semiconductor ETF

Meme stocks (especially those that have soared lately on debatably bullish news)

Bonds where the relevant common stock has broken multi-year support.

Long-term Treasury bonds yielding sub-4%

Profitless tech companies (especially if they have risen significantly recently)

Small cap growth

Mid cap growth

20230509